Games

PCB

Archive

Chip

Archive

Cart/Box

Scans

Articles

Peripherals

Prototypes

Unreleased

Games

Rarities

Homebrew

Emulation

Links

Email: snes_central@yahoo.ca

On video game preservationOn video game preservation |

| What does it mean to preserve video games? Here are some of my perspectives. By:

Evan G

|

SNES Central has been around for nearly two decades, and I would like to think I have been a part of video game preservation since its very infancy. Although I have always taken this to be a simple hobby that I focus on in my idle times, I think that, especially in the past 2-3 years, it is becoming a much more mainstream activity. The hardcore enthusiast scene has very much shifted from the "collect-em-all" mentality to one more focused on digital preservation. This new golden age, I think, is being driven by a cultural shift from the previous consumerism driven generation of those who came of age during the 60s to the 80s, to the millennial generation where physical objects are held in less esteem, and cultural objects are more transient. Having grown up in the late 90s, I was in the cohort when the Internet was starting to become a ubiquitous part of our life. This probably what influenced my decision to eschew game collecting and focus on preservation and documentation.

Conflicts

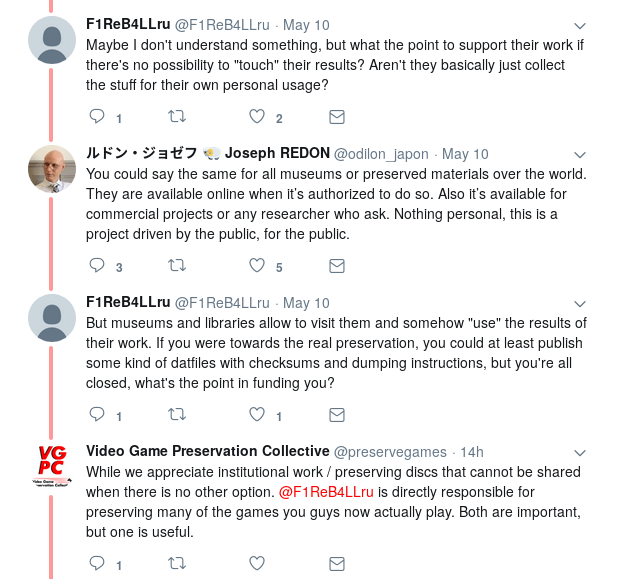

The impetus of this article was an exchange between Joseph Redon of the Japan-based Game Preservation Society and a couple of members of the Video Game Preservation Collective.

|

| Some tweets in this exchange |

The Game Preservation Society's (GPS) modus operandi is as follows:

We see games as an important asset and work to preserve it for future generations. Our members, although having various fields of expertise, overcome differences and share our knowledge to work towards the same goal. The preservation of video games carries many difficulties: scattering, neglect, obsolescence, vast amounts of data to handle... all making it an impossible task to take on as an individual. We strive to pass on to the world the knowledge that we gather. We need more people to help us, regardless of who you are. In return, we promise to do whatever it takes to preserve this important culture.

Meanwhile the Video Game Preservation Collective's (VGPC) is:

We focus on dumping / datting new roms for organized preservation databases like Redump.org and No-Intro. This is our core mission.

If we look this difference in views, we can see that the GPS acts more like a traditional academic institution, while the VGPC focuses on verifying the integrity of video game binary files through a more anarchic "all data must be free". The main conflict here is that, and this was told to me directly by an VGPC admin, that if the file is not in the databases, it is not considered to be preserved in the eyes of the VGPC.

Is No Intro preservation?

The first issue I have here is this. Is a database of file hashes that verify the integrity of a ROM or disc image truly "preservation"? I would argue that it is not by itself. I have no problem with the efforts of compiling the hashes of files into a database, and I think it is incredibly important. However, the existence of these databases of "verified" images as preservation is predicated on the idea that these files will be available somewhere for download. One big issue I have with this is that if a file is not in these hash databases, then these files will not necessarily be distributed. They purposely exclude hacks (No Intro's name is a testament to their mission to remove intro hacks), which themselves are academically interesting. In this case, I think that Cowering's Goodtools project was a much more complete dataset and was better for broadly preserving things (if the goal is to make a large collection of files). The second problem I have is that these hash databases do not necessarily record who did the act of verifying or how these files came to exist. I have a scene release file archive, and it is great because the original scene group files are still there, along with the date stamps on the files that tells you when they were made available. This doesn't even delve into the lack of preservation related actives like determining how the games change between localizations or bug-fix releases (like what is commonly done by The Cutting Room Floor).

The Role of Museums

Although the GPS is not strictly a museum, they operate as a more traditional academic institute dedicated to preservation. Their work goes much further than simply backing up a file and ensuring its integrity (and I guarantee you that they do this). They allow researchers to go and investigate the physical objects and companies to use these backups to keep the old games alive. You might argue that not enough companies do this, but there may come a point when it becomes increasingly prevalent. More importantly, since the GPS is a non-profit organization, they have the ability to gain access to materials that an enthusiast would never be able to. Those of us who do preservation activities as a mere hobby usually have to hope that something slips through the cracks (e.g. finding prototypes that were not destroyed), because few companies would ever willingly leak things out. Since they are an academic institution, the material is available for study, though it may not be as convenient as simply downloading it from the Internet.

The East-West cultural divide

One thing I have noticed is there is a lot of angst that the Japanese are far less likely to preserve games (and by that, they mean leaking the files onto the internet). Some historical perspective is in order. In the Anglosphere, our society evolved through hundreds of years of conflict, where governments were often overthrown by popular revolution. As a result, the state-level apparatus is relatively weak and people will often ignore rules if they find them unjust. In Japan, they have had a long tradition (stretching back at least 500 years) of a strong, centralized state with relatively few revolts. As a result, in Japan, there is a deep respect for the rules of the state, and people are not so willing to disobey the law. In the Anglosphere, especially the United States, there is less respect for the rules because there is less fear of retribution.

How does this relate to this topic? It all comes down to copyright law. Copyright law in the Anglosphere and Japan is pretty much the same - works tend to remain in copyright until long after the death of the original creator. Since most video games are produced by major companies by teams of people, this means that the copyright is essentially perpetual (at least in our lives). Few Japanese people are going to overtly break the law and leak out games, even though most people involved in game preservation understand there is effectively no penalty for it. This is why the GPS is so important, because they will be able to get access a large amount of material that will never fall into the hands of the amateur preservationist. Importantly, this material also becomes accessible to a researcher, which may not necessarily be true for files listed in the hash databases (which require access to the darker parts of the Internet).

The way forward

It makes little sense to snipe at each other's efforts in preservation - both have their place. The real enemy to preservation is perpetual copyright. We cannot and should not expect those who do preservation work to overtly break the law, even if it is commonly done. Copyright law, as it is now is designed, is entirely for the benefit large corporations that persist longer than the general lifespan of the average human. This is a perversion of the original intent of copyright law - which was to allow a creator time to profit from their efforts by granting a limited duration monopoly on the production of their work. Copyright law now does the opposite. It allows a company to smother the creation of new works by allowing them to profit from a work produced by people that have long since passed away, instead of incentivizing them to invest in new works.

In the Internet age, copyright law threatens the preservation of our culture, as files can easily disappear if a web service shuts down. Games themselves become harder to access as old hardware becomes obsolete, and new hardware cannot play the old files. This doesn't even cover the fact that many companies that made video games even 25 years ago when the SNES was still alive are now gone, and the owner of the copyright of certain games is unknown. Copyright law needs to be changed to accommodate this. I have argued that a default copyright length of 20 years, with the possibility of renewal for an additional 20 years (with a fee), would be sufficient for the vast majority of creative works. I would be willing to bet that if this rule was in place now, 80-90% of SNES games would already be in the public domain. The threat of losing the remaining 10-20% of games would probably be minimal, as those would be the Super Mario Worlds of games, which still are profitable and easily accessible.

The only way for things to change is to make change at the ballot box. The pressure needs to come from as many governments as possible, since copyright law is defined by international treaty. Like it or not, though, changes to copyright law is not going to be instigated by Japan, which will be ruled by a very conservative government for the foreseeable future. The change to perpetual copyright was driven by companies in the United States, and I think that it will have to be the United States that pushes for their reduction. Unfortunately, I can only see copyright law getting worse before it gets better, and it will remain that way at least until the Millennial generation starts taking control of the government.